LGBT History

Federico García Lorca and his Ode to Walt Whitman

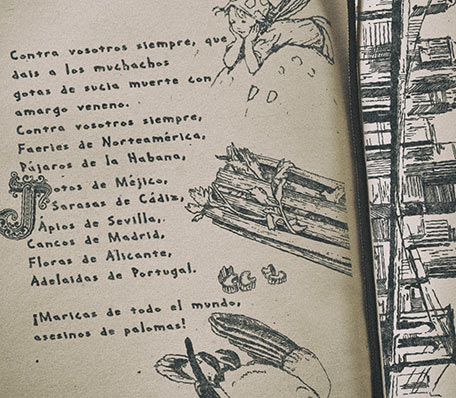

As we began our peculiar search for words, we soon found these phrases, which we later knew as verses from Federico García Lorca and his Ode to Walt Whitman.

“Faeries of North America, Pájaros of Havana, Jotos of Mexico, Sarasas of Cadiz, Apios of Seville, Cancos of Madrid, Floras of Alicante, Adelaidas of Portugal”

Faeries, pájaros, jotos, sarasas, apios, cancos, floras, adelaidas… are, synonyms of Marica (pansy, sissy).

The words remained collected in endless lists waiting to find their origin and explanation, until years later we have met again with the Apios of Seville, and as, in other occasions, we have opened a door to a world forgotten by the passage of time and by the firm determination to silence what really was the inseparable life and work of Federico García Lorca (1898-1936).

In this article, we are going to present our interpretation of the Ode to Walt Whitman, in which the murder of Maricas (pansies) is almost encouraged, being, therefore, a poem that generates some controversy and shock. In order to understand what Federico meant, we had to make a long journey through his life experiences, his lovers and his sexuality to know what kind of person he was, being detail in this case important. Bits and pieces from here and there have helped us to comprehend the full story of this child, young and homosexual man, filling the gaps which for other publications are enigmas, but for us are pretty obvious. We have walked on his shoes, and to do so, we have used the work of Ian Gibson, which we have complemented using newspaper archives, and plenty of information found on the net. This article is, therefore, a subjective exercise made from the certain facts that are known, about the person who wrote the Oda to Walt Whitman, and why he wrote it.

1 The sexuality of Lorca and literature.

It is important to notice that after his execution on that August 18, enormous efforts were made to erase the homosexuality of Lorca’s work, both by his family – lawsuits included – and by some actors in the publishing and academic sector. In this way, numerous specialized and highly reputed works have been written in which his work is studied, removing or avoiding homosexuality in the analysis, whereas in fact, Federico García Lorca practically did not speak of anything other than the conflict that his homosexuality entailed for him in a society as homophobic as it was. And this is demonstrated, not only by his entire work, which can be interpretable, but by the large number of letters, testimonies, biographies and interviews that go beyond doubts, and which show how his works were cooked and how Federico Garcia Lorca was built.

Yes, everybody knew that Federico was homosexual, and so we were told from a certain age when studying Literature. But nobody would even think, for example, that “Yerma” (Barren) (1934) deals with unfruitful, barren love, as the one that unites two men. Yerma is part of a projected trilogy together with “Bodas de sangre” (Blood Wedding) (1931) and “The Destruction of Sodom” also titled “The Drama of the Daughters of Lot” or “The Daughters of Lot”, a play that could not be written.

Nor did they tell us about the missing play “La bola negra. Drama de costumbres actuales” (The Black Ball. Drama of current customs), or “La piedra oscura. Drama epéntico.” (The Dark Stone. Epentic drama), thought titles for a play whose first scene counted thus:

“Una capital de provincia. Un señor tras una mesa de despacho. Llama al timbre y entra un criado:

—Que venga el señorito.

Entra su hijo.

—¿Qué quiere decir esto que sé? —y el padre muestra a su hijo una carta—. ¿Que te has presentado pretendiente a socio en el casino y te han echado bola negra? ¿Por qué?

—Porque soy homosexual.”

(A provincial capital. A man behind a desk. Calls the bell and enter a servant:

—Get my young son here.

Enter his son.

—What does this that I know mean?” — the father shows his son a letter—. You have applied to be partner in the Social Club and they have given you black ball? Why?

—Because I’m homosexual.)

This text today, in this world of diverse sexuality, may not draw attention. However, in the context of the 30s it was modern and revolutionary. It makes me dream of what a surviving Lorca could have meant for the LGBT protest movement in Spain, which began making its first steps 30 years later. It must be taken into account that with this text Lorca has not only gone beyond the more traditional poetry, which allows to tell and hide and the also unclear theatrical surrealism of “El público” (1930) (The Public), but he, without ambiguity, speaks of homosexuality in a more explicit and direct way.

2 Homosexual Lorca.

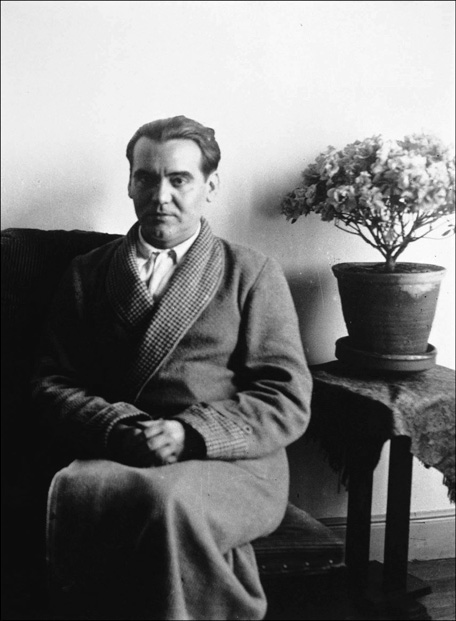

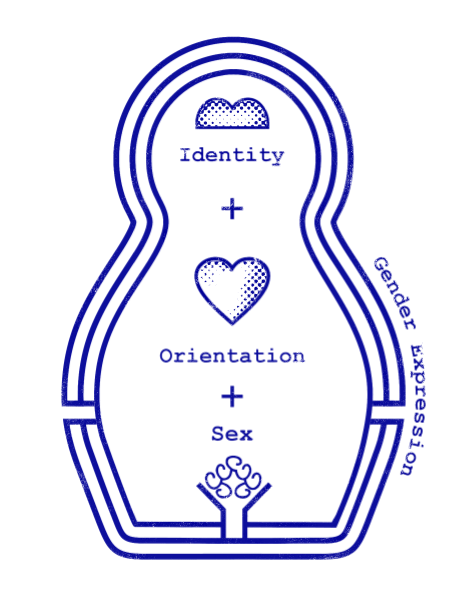

(1) Picture of the famous photographer Alfonso in April 1936 for the madrilenian newspaper La Voz, in which the poet’s “he-she” gender expression can be seen. In other words, a whole lady.

Federico García Lorca was an outside the closet homosexual man, everyone knew it. His friends, his family, his neighbors; and not only because he freely lived his sexuality, but also because during the last years of the republic, the right-winged media openly insulted and despised him and his successful work. For instance, instead of Lorca they wrote Loca (literally in Spanish language, crazy woman, but in slang, very effeminate man), and the next day it appeared in the erratum.

But it was not only a question of youth or adulthood. Already as a child the people who knew him noticed his effeminacy, such as his teachers and schoolmates, who gave him a hard time about it. Also his first love, Maria Luisa Nátera Ladrón de Guevara, a 14 year old girl, older than him, was conscious about it and did not like Federico because he was effeminate.

Lorca was not only a teased child, pubescent or effeminate teenager, but according to his own words, he monopolized the children already in his childhood. According to his friend Pepe Garcia Carrillo, Federico himself had recounted to him with insistence that when he was a kid in La Vega of Granada, he had “played” with all his mates.

«Mira, Pepe —decía Lorca—, cuando yo era así de pequeño, ya se la había meneado a todos ellos.» «Yo he estado con todos los chicos de Asquerosa», aseguraba.

(«Look, Pepe —Lorca said—, when I was this small, I had already jerked off them all.» «I’ve been with all the boys of Asquerosa», he claimed.)

And so, in his first prose he already tells us about semen, which according to the poet smells of summer and carnation. Absolutely evocative.

However, this homosexual and vital behavior was experienced by Lorca in a conflictive way, at least in the first part of his life. This was a time in which the unique referents, the idea, the concept of homosexuality, were as disease, crime and sin. Against this background, only the effeminate men were the visible ones, and for them that homo-uncultured society had a concrete role settled and some negative personal characteristics added to it. The Marica (pansy), a man who, among other things – being a coward, untrustworthy, stupid, mocked, etc. – desisted of love, as we shall see later.

However it is necessary to point out that the effeminacy of Federico was not obvious. There were people like Luis Buñuel, who did not realize it until other fellows of the Student Residence told him, even though the filmmaker was homophobic and had his fun hooking up with homosexuals in public toilets and then beating them up.

It is also quite probable that Federico made a certain effort to have a more masculine attitude. It was necessary, since being a Marica (pansy) was the worst of the worse. This was confirmed by the fact that there were people, even from the team of La Barraca, who did not have the slightest idea, and who had never suspected such a thing.

2.1 The men of Lorca

The life of Federico García Lorca was full of men, famous and anonymous, whose story is often lost in experiences, letters and sketches of works that have been hidden, destroyed and forgotten over the years. Both in Granada and Madrid and, of course, in the Americas, he was always surrounded by famous men, homosexual and not, with whom he shared experiences, longings, texts and / or sex. Yes, sex. Lorca liked masculine men.

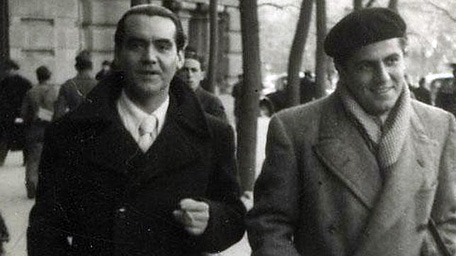

(2) Lorca and Rafael Rodríguez Rapún, heterosexual, mining student. He went from being secretary of La Barraca, to Lorca’s personal secretary, therefore “partner” of the poet from 1932-33 until his death, although he also met women. Addressee of the Sonetos Oscuros (1935) (Dark Sonnets), he enlisted in the republican front when Federico died. He let himself be killed in the northern front, precisely on the first anniversary of Frederico’s death. Three Rs was one of the reasons why García Lorca did not travel to America with Margarita Xirgu in January 36.

José García Carrillo and his brother Francisco, Adriano del Valle Rossi, Francisco Soriano, Luis Buñuel the homophobic, the enamored Emilio Prados, Gustavo Durán the macho, the complex Dalí, the hidden Rafael Martínez Nadal, the “bisexual” Emilio Aladrén, Eduardo Rodríguez Valdivieso, the shy Luis Cernuda, the sucking Cummings (allow me the joke), Leon Felipe, Luis Cardoza and Aragón, the soccer player Rafael Rodríguez Rapun, whom Lorca kissed in the park while putting his hand under his shirt, Eduardo Blanco-Amor, Vicente Aleixandre, Juan Ramón Jiménez, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, yes, the founder of the Spanish Falange. All these and many more are part, in one way or another, of the poet’s inner universe.

It is also necessary to take into account that Lorca died at age 38, still in his sexual fullness, so if Lorca saw someone he liked on the street, it did not matter if he was straight or not (or, especially if he was), he went for him and hooked up with him, as any young man could do today. Well, anyone who has that dizzying, charming, attractive and powerful personality that Federico had.

Despite his sexual conflict, what is very clear for anyone who can see is that Lorca was a very sexually active person, as evidenced by the large number of testimonies and documents of his own handwriting. Although many details remain deliberately hidden or lost, others have become famous, as when he tried to penetrate Salvador Dalí, at least twice.

What is less known is that in one of these occasions there were three people, the poet, the painter and a girl, Margarita Manso, a classmate of Dalí. Lorca tried to penetrate Dalí, but he could not, and then Lorca did the girl. The curious thing about the case is to know why Lorca tried to penetrate Dalí, supposedly straight, when according to Luis Antonio de Villena, Vicente Aleixandre, a great friend of Federico, told him many times about the “passive” pleasures of Lorca. And a second question, of which Dalí never spoke, what happened in the preliminaries that undoubtedly occurred?

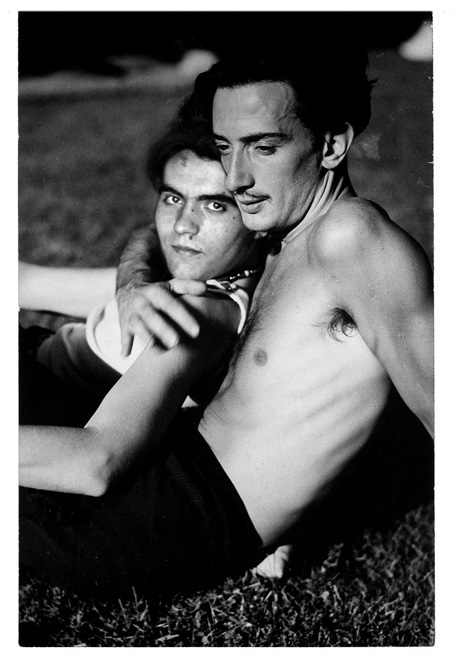

(3) Fake photo that helps us illustrate this fragment: “yo he vevido la muerte en tu espalda en aquellos momentos en que te ausentabas de tus grandes brazos” (I have lived / drunk the death on your back in those moments when you were absent from your great arms.” Letter from Dali to Lorca regarding the Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Ballads) (1928). The intentional misspelling in the original text, “vevido”, can be read as lived or drunk. The phrase can not be more descriptive.

And not only there was sex as is natural, there was also love and infatuations, and even, polyamor. The modernity of Lorca lies not only in obviating de facto homo and hetero labels, but also in having non-exclusive love. Dalí, Emilio Aladrén, Eduardo Rodríguez Valdivieso, and Rafael Rodríguez Rapún were, in this order, the great and sometimes overlapping, known loves of Lorca.

2.2. Lorca the epentic

In order to talk about the sexuality of Federico García Lorca, it is necessary to speak of the use of language, of epentism and epentics, which are nothing but language in code and, basically, a kind of joke invented by Lorca from a figure of diction, the epenthesis, which has in many occasions and as a consequence, varying the position of one letter putting it behind another, that is, according to the poet, fucking its ass.

Epentism means homosexuality and Epentic homosexual. In this way they could talk about the subject without anyone knowing what it meant, but it was also possibly a way to have fun and to create a term that was not an insult or did not have the connotation of mental illness of the word homosexual at the time. A sample of all this is the letter that an unleashed Rafael Martínez Nadal writes to Federico, telling him that he wants to leave his career to become masseur of a sports club in Madrid:

«¡Qué solarium de “torsos yacentes”! ¡Qué de músculos distendidos! Para llorar. Tú también llorarías. Es imposible soñar más bellezas reunidas ni más epentismo flotante.»

(What a solarium of “lying torsos“! So many distended muscles! To cry for. You would cry too. It is impossible to dream of more gathered beauties nor more floating epentism.)

Another interesting point of the use of the language in the most intimate relations was to call each other in feminine way, something pretty frequent in the actual times. Federico, Martinez Nadal and Garcia Carrillo, mutually called themselves godmothers.

As in all people, sexual identity as a whole ends up being expressed in different ways. And in the case of Lorca, in addition to being a conflict, it was also a source of relaxation and fun. Talking in feminine, and perverting the language, are proof of it.

Nevertheless, we can distinguish two Lorcas, the one before his trip to New York and the one after his stay in the Americas and Walt Whitman.

3 Ode to Walt Whitman. Lorca’s homophobic poem?

It is quite probable that Federico García Lorca had encountered the work of Walt Whitman (1819-1892) many years before, but many people think it was through Leon Felipe that Lorca made a more significant approach to Whitman. He lived in New York and was the translator of Whitman’s work. Lorca frequented him during his stay In New York. This approach that was vital and could be the resolution of his inner conflict with homosexuality.

Put yourself in the skin of young Lorca, epentic he-she, frequently horny, who could disappear at any time to go cruising. Fuente Vaqueros, Asquerosa, Granada, Madrid, Paris, London, New York. That search, that attempt to understand, build and love oneself. Am I what I hate? Widening horizons sure was a good revulsive for him.

(4) Emilio Aladrén Perojo, with whom Lorca had a relationship (1928-29) that more or less ended when he became engaged to his wife Eleonor Dove. Very sexually active and lover of the “good life”, he ended up being the sculptor of the pro-Franco regime.

The 31-year-old poet who arrived in New York saddened by the abandonment of Dalí and Emilio Aladrén, frequented gay bars and enjoyed orgies with black people, sailors and soldiers, as well as lectures and talks. Although we must not ignore the delicate situation of homosexual men in North America at the time, Garcia Lorca, famous, admired and with means, could enjoy a freedom which was unthinkable in Spain.

Thus, during his return to New York after his stay in Cuba – three Cuban lovers are known -, Lorca finalizes his Oda to Walt Whitman, poem pertaining to his work “Poet in New York” (1930). A poem, published in life, often called Lorca’s homophobic poem, due to the following verses:

[…]

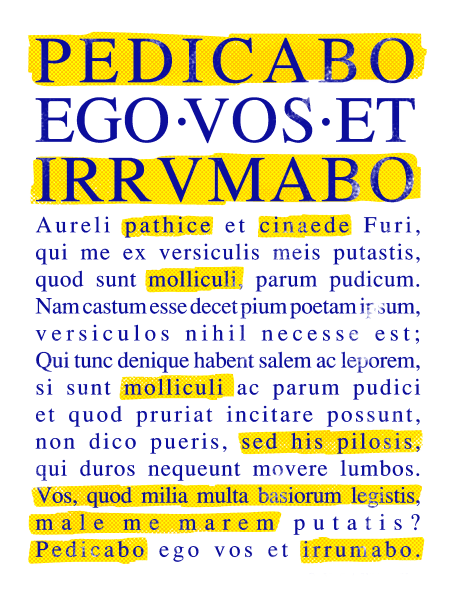

Por eso no levanto mi voz, viejo Walt Whitman,

contra el niño que escribe

nombre de niña en su almohada,

ni contra el muchacho que se viste de novia

en la oscuridad del ropero,

ni contra los solitarios de los casinos

que beben con asco el agua de la prostitución,

ni contra los hombres de mirada verde

que aman al hombre y queman sus labios en silencio.

Pero sí contra vosotros, maricas de las ciudades,

de carne tumefacta y pensamiento inmundo,

madres de lodo, arpías, enemigos sin sueño

del Amor que reparte coronas de alegría.

Contra vosotros siempre, que dais a los muchachos

gotas de sucia muerte con amargo veneno.

Contra vosotros siempre,

Faeries de Norteamérica,

Pájaros de la Habana,

Jotos de Méjico,

Sarasas de Cádiz,

Ápios de Sevilla,

Cancos de Madrid,

Floras de Alicante,

Adelaidas de Portugal.

¡Maricas de todo el mundo, asesinos de palomas!

Esclavos de la mujer, perras de sus tocadores,

abiertos en las plazas con fiebre de abanico

o emboscadas en yertos paisajes de cicuta.

¡No haya cuartel! La muerte

mana de vuestros ojos

y agrupa flores grises en la orilla del cieno.

¡No haya cuartel! ¡Alerta!

Que los confundidos, los puros,

los clásicos, los señalados, los suplicantes

os cierren las puertas de la bacanal.

[…]

[…]

That’s why I don’t raise my voice, old Walt Whitman,

against the little boy who writes

the name of a girl on his pillow,

nor against the boy who dresses as a bride

in the darkness of the wardrobe,

nor against the solitary men in casinos

who drink with revulsion prostitution’s water,

nor against the men with green look in their eyes

who love other men and burn their lips in silence.

But yes against you, maricas from cities,

tumescent flesh and unclean thoughts,

mothers of mud, harpies, enemies without

dream of Love that gives crowns of joy.

Against you always, who give boys

drops of dirty death with bitter poison.

Against you always,

Fairies of North America,

Pájaros of Havana,

Jotos of Mexico,

Sarasas of Cádiz,

Apios of Seville,

Cancos of Madrid,

Floras of Alicante,

Adelaidas of Portugal.

Maricas of the entire world, murderers of doves!

Slaves of women, their bedroom bitches,

opened in public squares with feverish fan

or ambushed in rigid hemlock landscapes.

No quarter given! Death

spills from your eyes

and gathers gray flowers at the mire’s edge.

No quarter given! Attention!

Let the confused, the pure,

the classical, the pointed, the supplicants

close the doors of the bacchanal to you.

[…]

Lorca did not raise his voice against the boy who wrote the name of a girl on his pillow, a transgender girl, or against the boy who cross-dressed in solitude, or against men who are looking for hustlers, or against those who love and desire another man without being able to say it, but he did against the Maricas.

He even urged the Maricas to die in a draft of these last verses, written in the margin in the manuscript of the poem, published by Rafael Martínez Nadal years later:

“No haya cuartel

matadlos en la calle

con bastón de estoque.”

(No quarter given

kill them on the street

with sword cane.)

What did Lorca have against maricas? As we shall see below, specifically nothing, and in the abstract, everything.

4 Lorca and the referents.

We have already spoken on many occasions of the performative character of the insult, of how referents construct people’s lives in their image and likeness. At the time Lorca lived the homosexual referent was the Marica (pansy), and Lorca’s effeminacy “hopelessly headed towards” him to become one.

The marica was that effeminate and harmless man, surrounded by women and mocked, that man who was like a woman and who ended up behaving like one (stereotypically negative), that renounced to love – enemigos sin sueño del Amor que reparte coronas de alegría (enemies without dream of Love that give crowns of joy) -, a man without sexual life or settled for more or less mercantile, sporadic, hidden and / or perverse sex.

The marica was the role that the society of that time had reserved for effeminate homosexual men. They were the only existing ones because they were visible, and they were endowed with the worst flaws. They were not expected, nor conceived, to be able to aspire to meet, fall in love and live life together with another man.

And Lorca had a problem with this. Since he was not straight, he was a marica and did not want to be one. – Is this what I am supposed to be? Am I to behave like that? Will my life be like this? –

Everything changed with Whitman because Lorca found a new referent in him. The virility, the fraternity and camaraderie, the admiration of the masculine body, the self-acceptance and self-expression, the claim of homosexuality, the defense of the oppressed and the exploited are, in essence, the characteristics of a new referent that finished building Federico, providing coherence to his reality and his aspirations.

With this new referent, Lorca was able to kill the previous one, change his suit and body. This is what the “Ode to Walt Whitman” means, the abandonment and destruction of the only existing referent, the label that made him suffer so much, the assumption of a new one and the announcement of better times with “la llegada del reino de la espiga” (the arrival of the kingdom of the spike). There is no homophobia, just the opposite.

5 Gay Lorca, the lost reference.

And so we can imagine Lorca, at age 31, in New York, successful, with money and with Whitman. He unchained himself. Both personally and literally. Lorca returned from New York and his subsequent stay in the Americas, morphed into another person, less repressed and sexually confident. And this, added to its work in “La Barraca” and other questions, made him confront its adversaries much more. On one occasion, visiting a casino in Granada with Blanco-Amor, a parishioner approached them and said:

«Dicen que ustedes los poetas sois maricones.»

Y respondió Federico: «¿Y qué es poetas?»

(It is said that you poets are faggots.

And Federico answered: “And what is poets?)

The model of homosexuality exhibited by Lorca was absolutely revolutionary for the Spain of that time. He was a man who liked men, who sought relationships with men, and who fell in love and lived his life with them. In other words, what we consider logical and normal today. A homosexual man who showed himself as such and sought the same as the rest of the people, and who was not going to settle for the crumbs that society had reserved for him. A man of success, admired and loved, talented, charming and, therefore, envied and hated by many. An author absolutely committed to his society and determined to contribute to its transformation. That is, a danger.

Federico García Lorca, there’s no doubt about it, was killed for being a Maricón (faggot), not a Marica (pansy), a homosexual man who did not accept the role that society had reserved for him even if he suffered for it and which therefore questioned the model of society. A maricón beloved by many people in the world. A brave, successful and envied maricón.

And this is exactly what, in essence and almost unconsciously, those who murdered him wanted to avoid and avoided, and this is what maybe the rest of us missed, a creative, proud and claiming Gay Lorca, which for many would have been, without a doubt, a new referent.

Sources and credits: Final translation by Ruth Carballo Gallego. “Lorca y el mundo gay” Ian Gibson, (Ediciones B, 2015). Publications by Luis Antonio de Villena Publications from ABC, El País, El mundo, RTVE Pictures of Federico García Lorca fundation and others, founded on Internet. Interesting links: Ode to Walt Whitman.Tag :Heterosexuality, Homophobia, Homosexuality And leave us a comment

Something to say?

Tell us what you think of this article. If it’s good or bad, if you think we are idiots, or if you see us in hell. Even if you are a few words person, you can do something to improve people’s lives, helping us to spread it.

Share it in your networks!